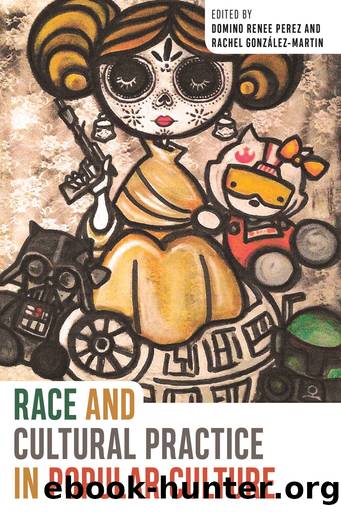

Race and Cultural Practice in Popular Culture by Domino Renee Perez Rachel González-Martin

Author:Domino Renee Perez, Rachel González-Martin [Domino Renee Perez, Rachel González-Martin]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Nonfiction, Social & Cultural Studies, Social Science, Cultural Studies, Popular Culture

ISBN: 9783030394196

Publisher: Springer International Publishing

Published: 2020-04-04T04:00:00+00:00

Notes

I wish to thank Claire Fox, who was instrumental in the conceptualization and early writing of this chapter. I am indebted to her guidance and mentoring. I am fortunate to have seen both Downs (May 2007 in Madison, Wisconsin, October 2012 in Iowa City, Iowa, and October 2012 in St. Paul, Minnesota) and Hadad (May 2007 in Mexico City) perform live, which I highly recommend for anyone studying U.S./Mexican intercultural studies. As someone who has personally dealt with identity negotiation, I thank these artists for continuing to inspire me.

â â 1â â â Though Downs and Hadad are not performance artists per se their work can be described as performative. In this analysis I make use of Richard Schechnerâs broad and inclusive definition of performance, which reads that âperformance must be construed as a âbroad spectrumâ or âcontinuumâ of human actions ranging from ritual, play, sports, popular entertainments, performance arts, and everyday life performances to the enactment of social, professional, gender, race, and class roles, and on to healing and shamanism, the media, and the internet.⦠The underlying notion is that any action that is framed, presented, highlighted or displayed is a performanceâ (2). Schechner differentiates between what is a performance piece and what can be studied or seen as performance. My analysis stems from the latter.

â â 2â â â Greater Mexico, a term coined by Américo Paredes in his 1958 study With His Pistol in His Hand, was initially used to describe the American Southwest or the U.S.âMexico border, an area that Gloria Anzaldúa later named the Borderlands. The concept of Greater Mexico was further explored by José Limón, in American Encounters, who explains that the term ârefer(s) to all Mexicans, beyond Laredo and from either side, with all their commonalities and differencesâ (3). Héctor Calderón calls it âAmérica Mexicanaâ in his book Narratives of Greater Mexico, in which he studies the work of Chicano writers and their incorporation of the Borderlands in their work either as a location, as a subject, or as a framework. In âExpanding the Borderlands,â Lynn Stephen suggests that due to current scholarship the term Greater Mexico may be used broadly to incorporate other cities within the United States that have large populations of Spanish speakers of Mexican heritage, like Chicago, New York, or Philadelphia

â â 3â â â Jenni Rivera is an example of a female corrido singer who resisted the male-dominated perspective within the genre with songs like âLos ovariosâ and âJefa de Jefas.â Rivera included a corrido rendition of La tequilera in her album Mi vida loca. The fact that she recorded the song as a corrido is not surprising for two reasons: (1) it is the genre for which she is most well known; (2) as an American singer with Mexican ancestry who asserts her identity from within the borderlands, this northern genre makes sense.

â â 4â â â All translations are my own.

â â 5â â â See La tequilera by Semichon and Favre.

â â 6â â â Susana Vargas Cervantesâ âPerforming Mexicanidad: Criminality and Lucha Libreâ highlights the limits of Mexican masculinity and femininity. It focuses on âredressing the raced, classed, gendered and sexualized limits of mexicanidadâ (2).

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32533)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31931)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31920)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31905)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19023)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15899)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14470)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14041)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13836)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13335)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13324)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13218)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9304)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9264)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7483)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7295)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6733)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6602)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6252)